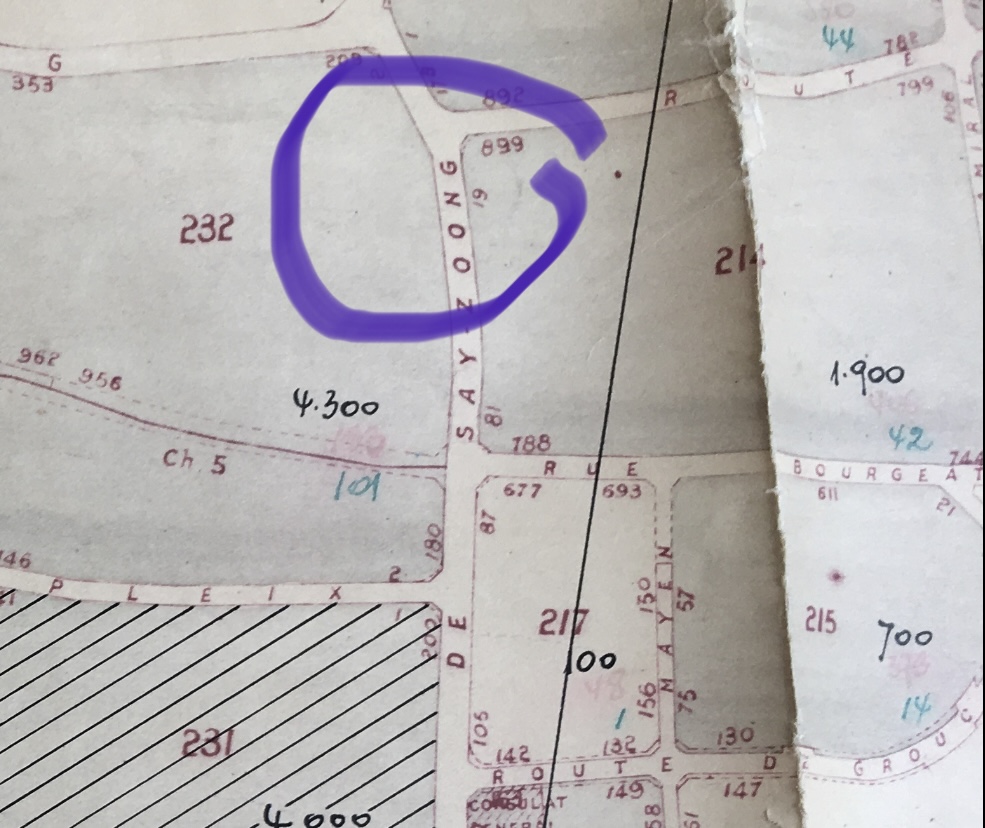

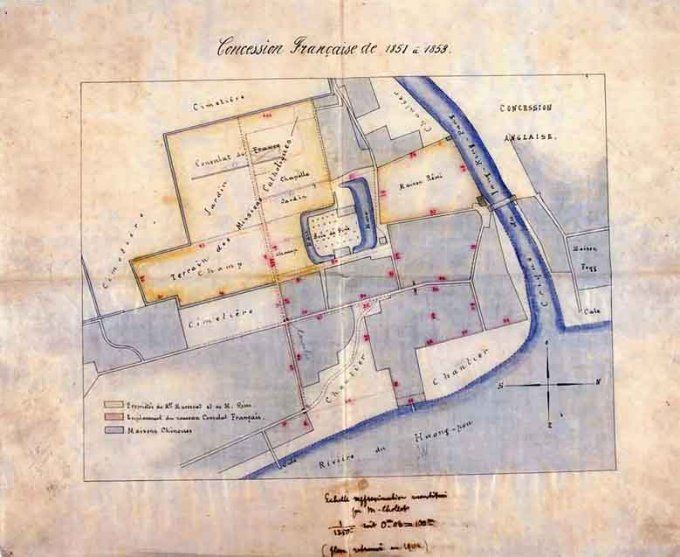

Maps are an essential took for understanding history. I recently found an amazing map of the Shanghai former French concession. Finding all information on it is a real challenge, but also very rewarding.

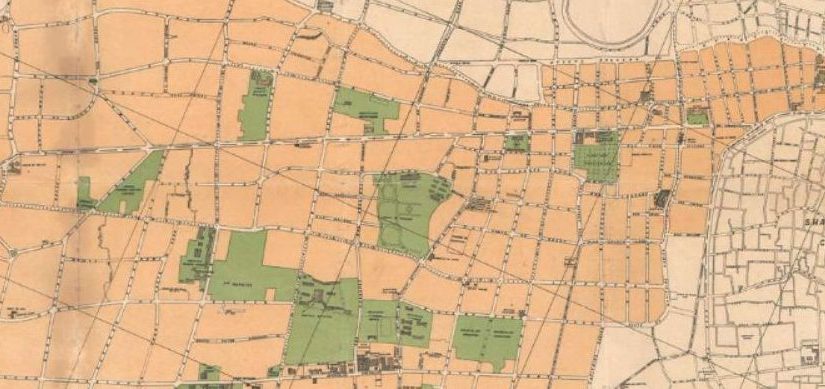

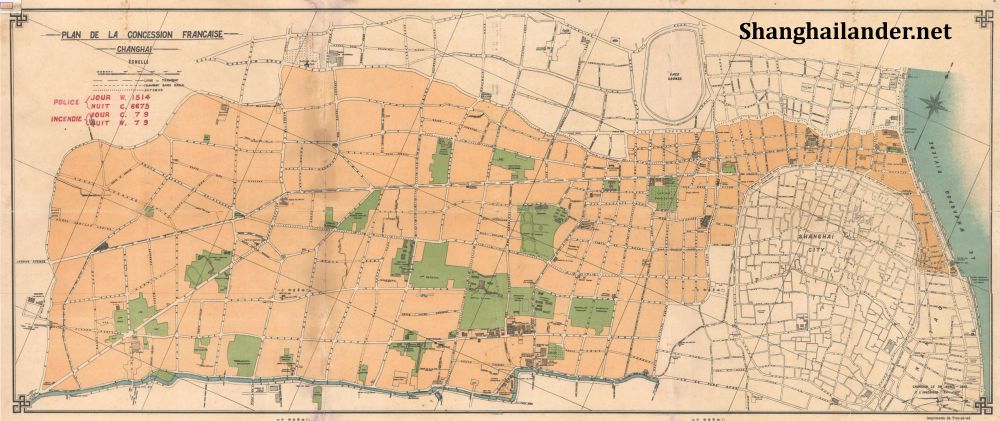

The below map was downloaded from a public website. It is clearly the scan of an historical map of the Shanghai French Concession. The title is “Plan de la Concession Française”, “Changhai”. The website mentioned the date of 1920, but it’s clearly from a later date.

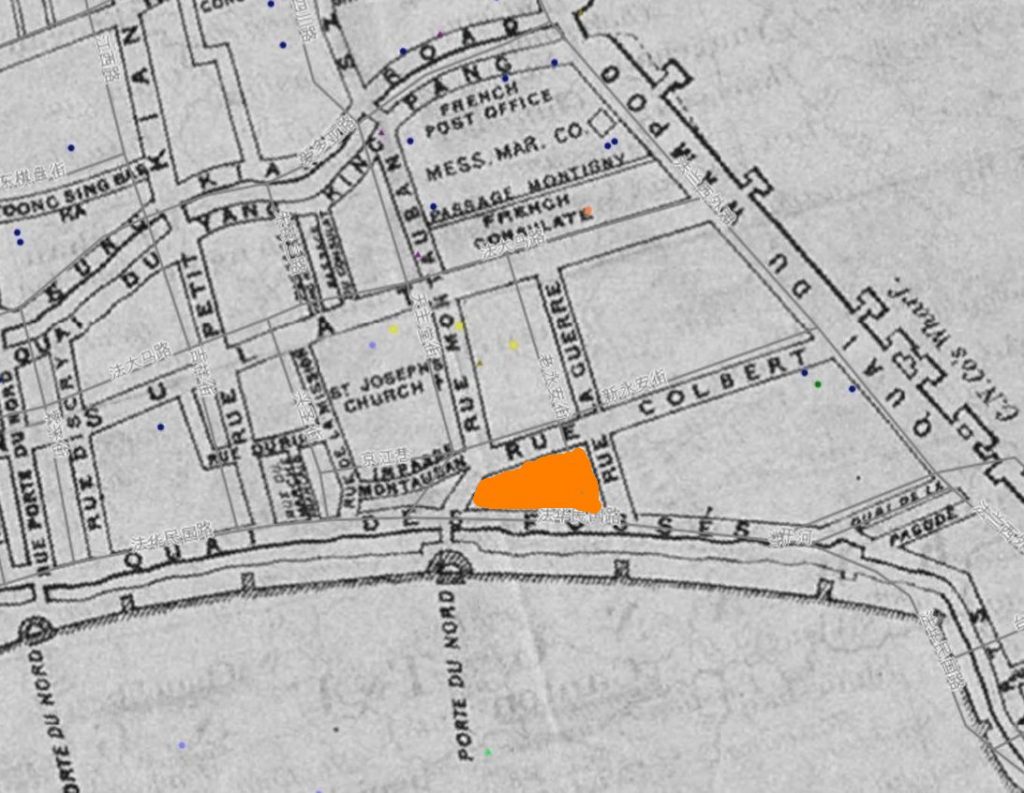

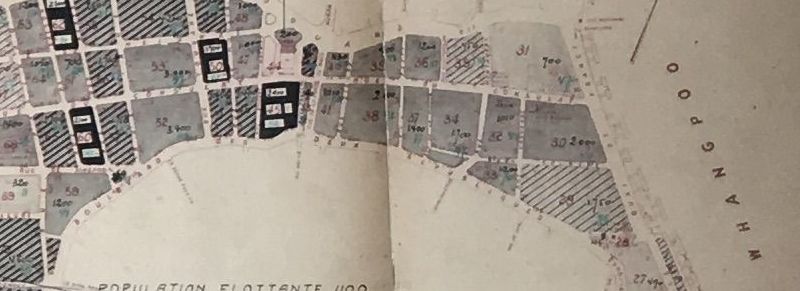

The shape of the map clearly shows the full size of the former French concession, after 1911. One specific point for finding the date of the map is the presence of the Cercle Sportif Français (Corner Route Bourgeat and Rue Cardinal Mercier / today Changle Lu and Maoming Nan Lu) , officially opened at the end of 1926. At the same time, the Canidrome is not mentioned on the map, in the block Route Lafayette / Route Cardinal Mercier / Avenue du Roi Albert (Fuxing Lu / Maoming Nan Lu / Shaanxi Nan lu). The part of the Rue Cardinal Mercier next to the canidrome was not even built, with the Morris Estate covering both side of the current Maoming Lu. As the Canidrome opened in 1928 and needed some time for building, the map can be dated from 1927.

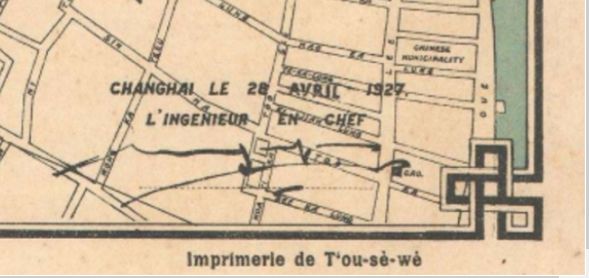

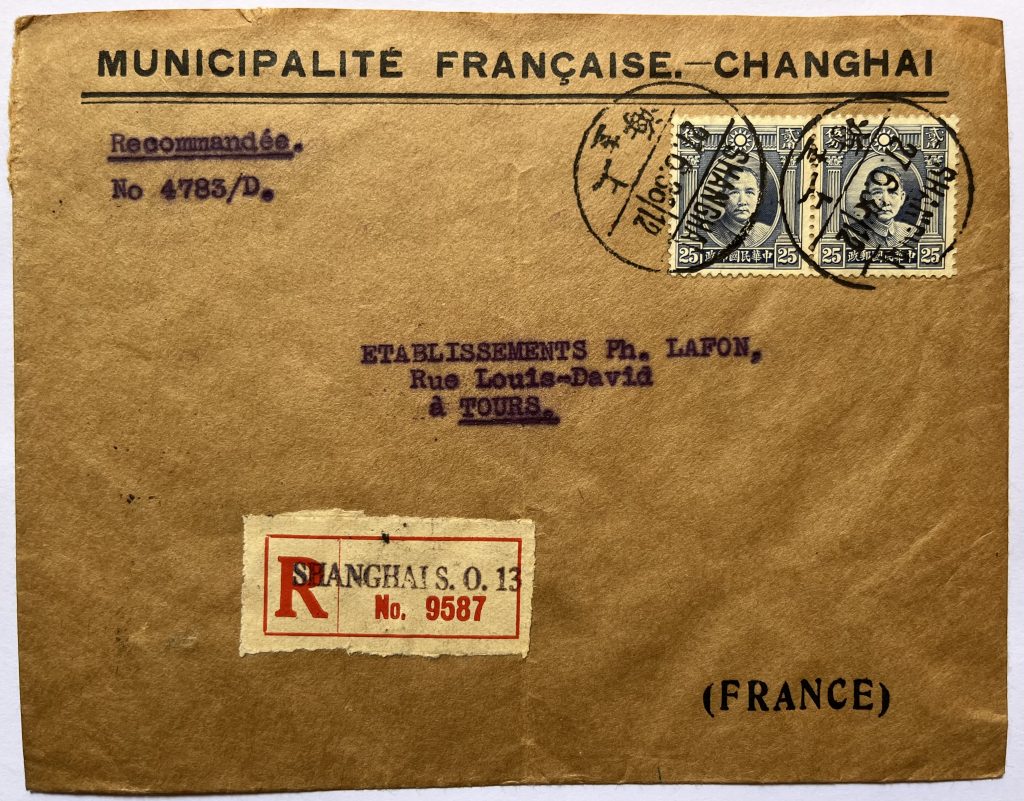

Looking at the details more in-depth, very interesting information is found in the lower right corner. First of all, the date of the design is written. The map design was finalised on 28 April 1927, by “l’ingénieur en chef” (the chief engineer) of the Shanghai French Municipality whose signature is printed on the map. Furthermore, the print work is mentionned as “T’ou-sé-Wé”. This was the orphanage of the ZiKaWei (XuJiaHui) Jesuits complex which was also an art and craft school run by the Jesuits priests. The framing of the map is also very nice, with a square motive on each corner. The map was printed on brown paper with 4 color (Black, Orange, Blue, Green).

On the top left corner is added some information probably stamped later in red. “Police Jour C 1514 / Nuit W 6675” as well as “Incendie Jour C 79 Nuit W 79”. I guess those were the police and fireman phone number for day and night service.

The size of the map is mentioned to be 12 x 28 inches (30.48 x 71.12 cm), with a 1 : 8750 scale. I am somewhat skeptical of a map size in inches, this must be an approximation as this French map was surely an integer number in cm. Futhermore, I have seen a very similar French Concession map, with original map about 140 cm x 60 cm).

This map is very highly detailed and of very high quality. Since it is signed by the chief engineer, it was made for the French Consulate, or most probably the French Municipality. This makes it an official map of the French Authorities. Those cadaster maps are extremely rare nowadays, this was a lucky catch. If you need the original full size file, download link is below.