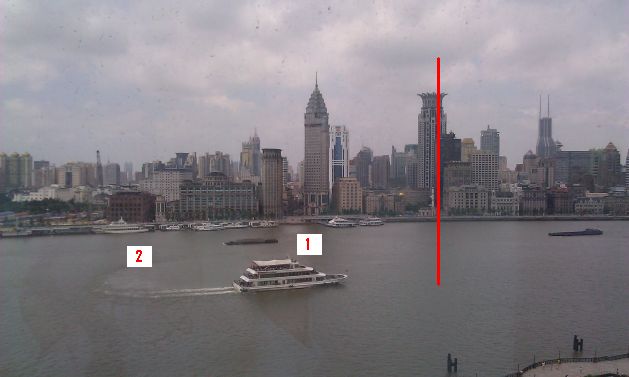

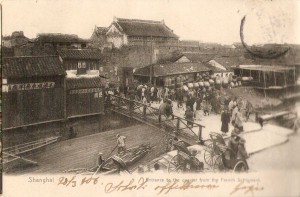

When Georges Balfour, the first Consul in Shanghai arrived in 1843, after the signing of the treaty of Nanking, what is now the Bund was very different from today. The world Bund comes from colonial india, meaning a mud bank on a river. On those early days of Shanghai, this is just what the Bund was, a mud bank over the river.

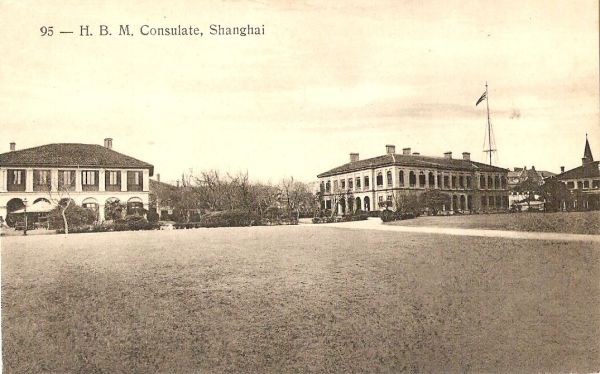

The area of swamps between the Suzhou Creek and the filthy Yang Jin Bang (to be later covered and turned to Avenue Edward VII, or Yanan Lu today) was granted to the Brits to make their settlement. They had already realized the importance of the mouth of Suzhou Creek going into the Huangpu river as a strategical place, by being bombed from this point during an exploratory trip in 1832. Naturally, this crucial point became the ground of the HBM Consulate, representing the British Empire in Shanghai.

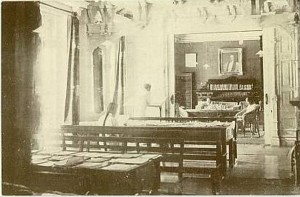

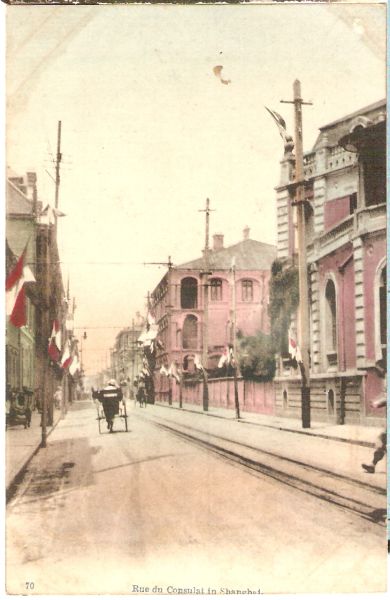

The current building along with the consul residence next to it was completed in 1873. It is one of the oldest building on the Bund, having survived the various reconstructions of the area. It was used as the British Consulate until 1967, when the consular staff was chased out during the Cultural Revolution. It then became a friendship store, before being abandoned. One of the buildings in the compound (left on the period photo) has been knocked down to make way for the Peninsula hotel, but the rest of the compound has been skillfully renovated. The Park was open to the public at the beginning of 2011 and it is now possible to cross the former Consulate Park to reach Yuan Min Yuan Lu and the Rock Bund project, making it a really nice walk.

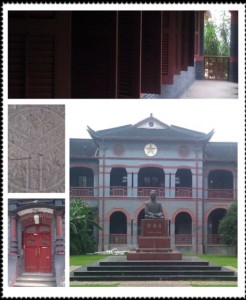

The external renovation has been very careful, keeping the original appearance of the building. It has been transformed into the “Financiers Club”, closed to the public so it is difficult to judge the internal renovation. The complex is managed by neighboring Peninsula hotel and used for functions. I heard one of the buildings will be transformed into luxury shopping center (what a surprise!). In any case, the renovation of the former British Consulate is quite a success, managing to preserve the atmosphere of one of the oldest remaining building of old Shanghai. Hopefully, many more will follow.

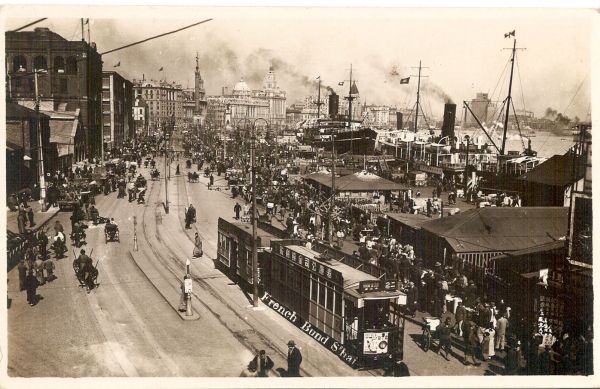

To read the post about the former French Consulate in Shanghai, follow this link.