After 3 years in the making, the first TV series of Wong Kar-wai (王家卫) has finally been released in the first days of January 2024. 繁花 (Shanghai blossoms) in English has taken like a storm. The TV series was broadcasted every night for 15 days, with 2 episodes / night. It was simultaneously available on online platforms. Every body has watched “繁花“,and everybody has watched it and everybody is talking about it. Focused on 1990s Shanghai, it is a little far away from this blogs topic, but definitely worth a post.

Shanghai born Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai 王家卫 is mostly known outside of China for the 2000 movie “In the mood for love” 花樣年華 that was nominated for Palm d’Or at Cannes festival 2000 and for which main actor, Tony Leung, won best actor. The move is also famous for its unforgettable soundtrack. Set in Shanghai in the 1990s, this new TV series offers quite similar dark atmosphere and visuals with many night scenes and and great music.

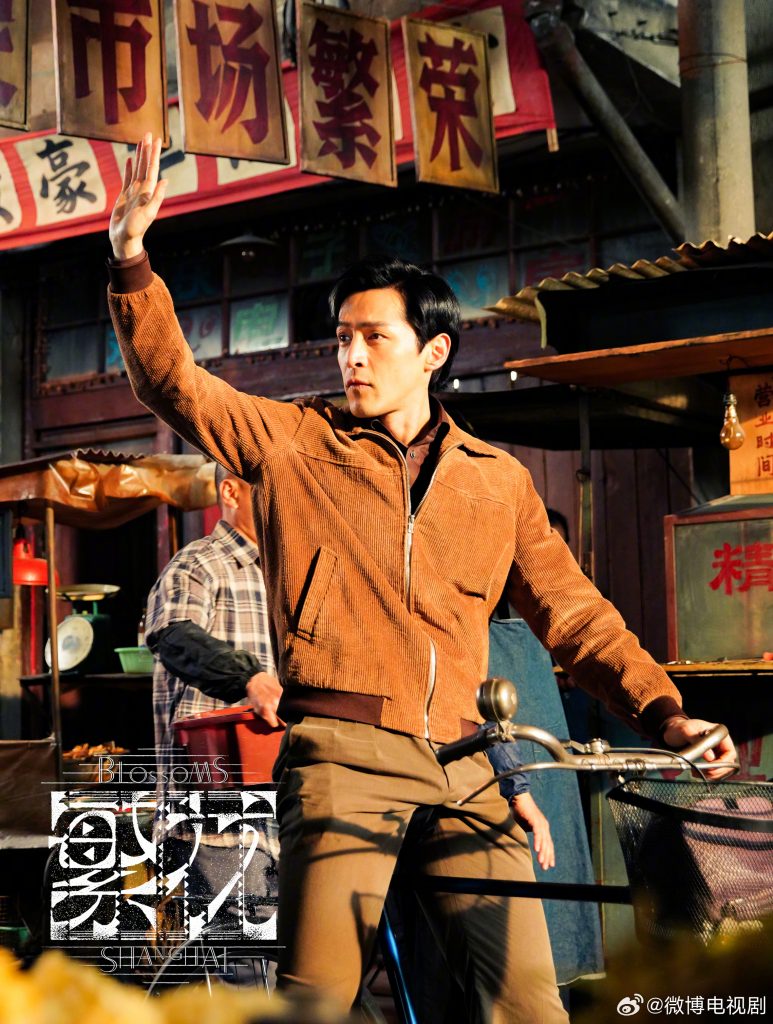

Taking place in Shanghai, it was filmed in Shanghainese dialect (shown with Chinese subtitle). Casting required most actors to be able to speak Shanghainese, who later dubbed a version in Mandarin that will be easier to understand by the rest of China. In a similar way to 2020 movie “B for busy” 爱情神话 (follow this link to original post about the movie), it particularly resonates with Shanghainese people. Shanghainese language has been on the decline in the last 30 years, so seeing major movie in Shanghainese language is an attraction. For more information about it, best is to read the article on English language magazine sixth tone by following this link https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1014442

A lot of energy was spent in collecting iconic objects for the 90s, including cars (mostly Volkswagen Santana), portable phone, cloths and other items, recreating a realistic Shanghai 90s picture. The story is based on a book of same name, inspired by real events from the 90s. The series really encapsulates the energy and craziness of 90s Shanghai, in a time that is not so crazy anymore. This reminds me a lot of about craziness and energy about Central Europe in the 90s, having lived both in Shanghai and Budapest in the 90s, I could see a lot of similarities. I am sure the series will be shown on tv outside of China. Watch for “Blossom Shanghai” when it comes.

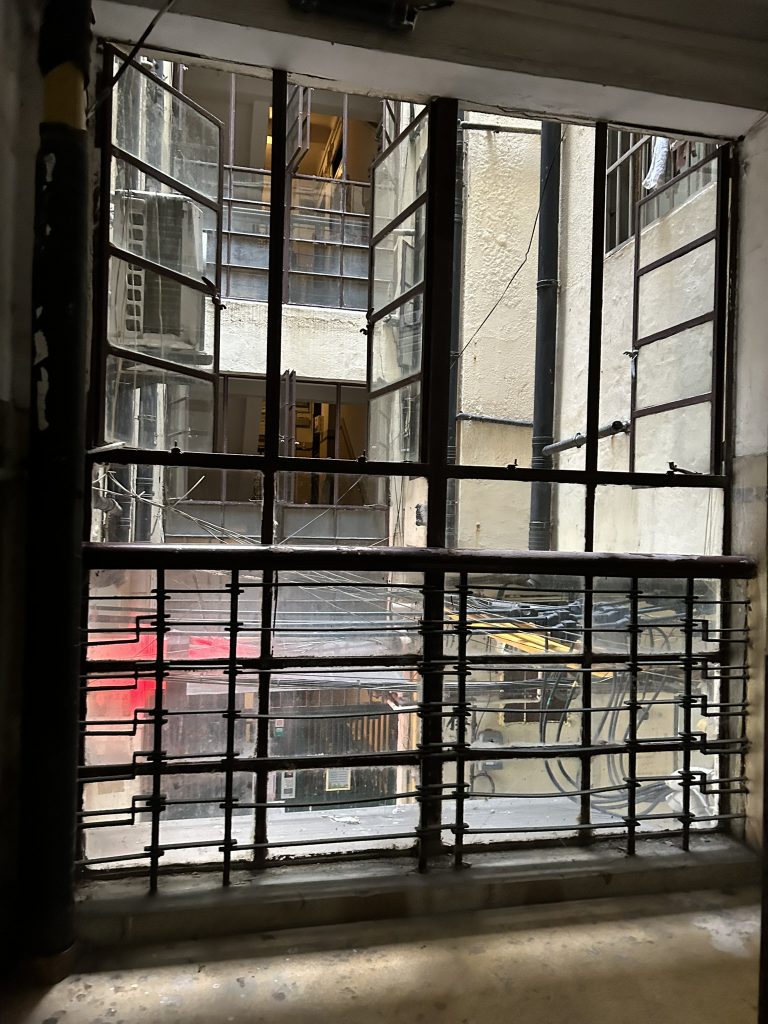

Although the series was filmed in a purpose built decor in Shanghai film studio, where I went for a visit a number of years ago (see post “Shanghai cinema studio“), the story takes place in real Shanghai locations. Huang He lu, 黄河路 a former hyped street behind Park Hotel that had become totally sleepy after the 90s has become crowded with young people taking selfies.

The English room of Peace Hotel (former Cathay Hotel) where part of the action also takes place is now booked for months in advance by people willing to recreate the experience of being there. Many restaurants now serve special “繁花” with food inspired by the series. Hopefully the hype will create interest in Shanghai history and help Shanghai preservation.